Memoization with Fibonacci and Collatz Sequences

What is memoization? Simply put, memoization is the process of designing a program to store intermediate results to make it more efficient. Especially in a situation where we have a recursive function or where costly computations would need to be repeated several times, memoization can greatly speed up our calculations. Here I will outline this process in Python using the Fibonacci and Collatz sequences as examples.

The Fibonacci sequence - A naive implementation

The Fibonacci sequence is easy to describe in words. We start with the initial values 0 and 1, then each successive term is calculated by adding the last two terms. We have:

\[\begin{align} F_0 &= 0\\ F_1 &= 1\\ F_n &= F_{n-1} + F_{n-2} \end{align}\]

The first few terms of the sequence are:

\[ 0,\;1,\;1,\;2,\;3,\;5,\;8,\;13,\;21,\;34,\;55,\;89,\;144,\; \ldots \]

We can easily see the recursive nature of this sequence. We have \(0+1=1\), \(1+1=2\), \(1+2=3\), \(2+3=5\), \(\dots\), with this pattern continued indefinitely. We can easily define this function in Python:

def fib(n):

if n == 0:

return 0

elif n == 1:

return 1

else:

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

Let’s take a look at the performance of the function by calculating the first fifty terms in the sequence and recording the times for each function call:

from time import time

times = []

for n in range(50):

start = time()

fib(n)

stop = time()

duration = stop-start

times.append((n, duration))

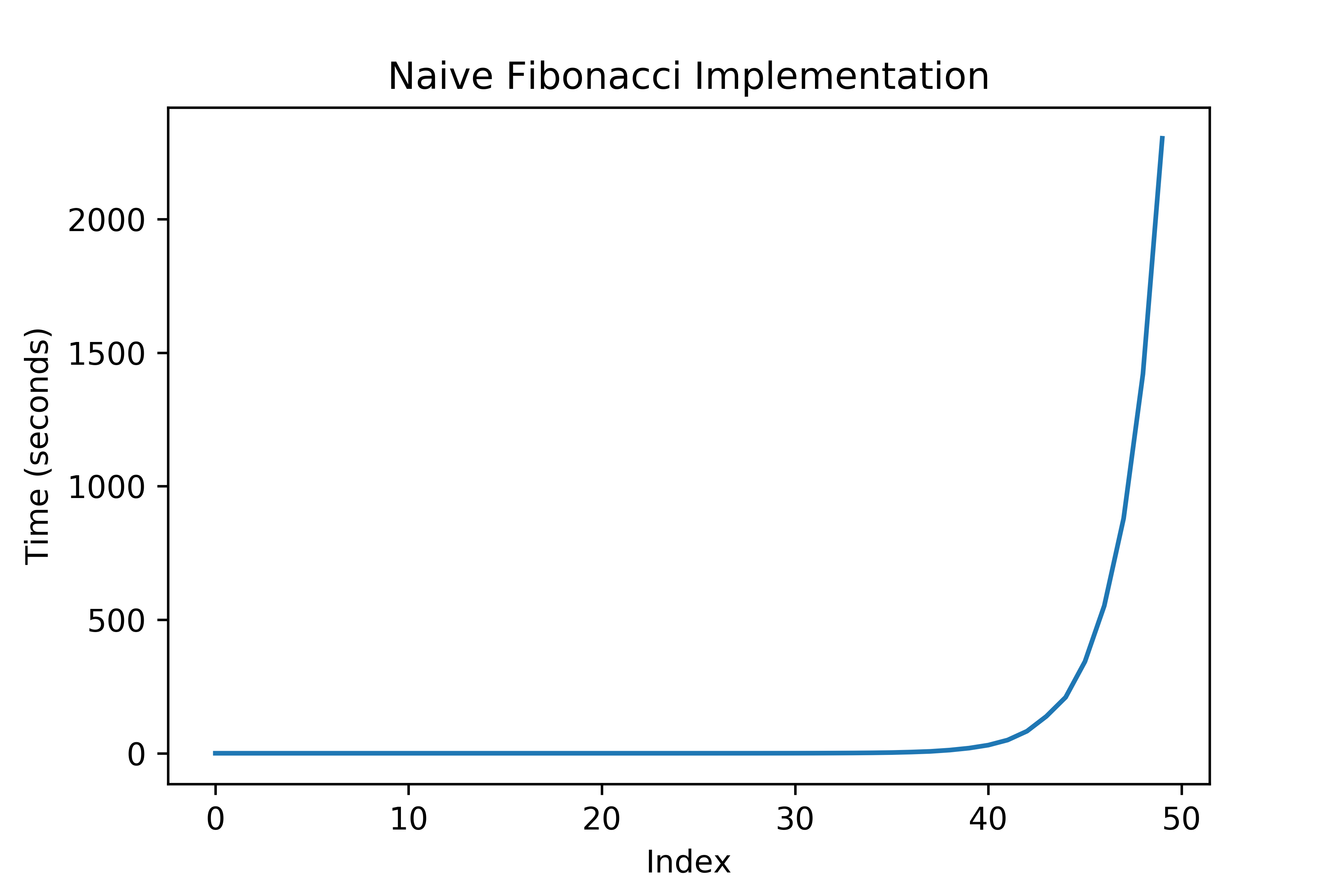

Looking at a graph of these times:

What’s going on here? We’re just adding numbers, something that shouldn’t be that expensive of an operation, but our execution times are huge and seeing what looks like exponential increase. In total this took over an hour to run on my desktop!

The problem is with the way that we have defined our function. By directly utilizing the recursion of the Fibonacci sequence in a function call, we have inadvertently made many more calculations than

are needed. For instance, let’s think about what is happening when we call fibs(5). Python does the following calculations, where each line roughly represents a step in the recursion:

\[\begin{align} \text{fibs}(5) &= \text{fibs}(4) + \text{fibs}(3)\\ &= \text{fibs}(3) + \text{fibs}(2) + \text{fibs}(2) + \text{fibs}(1)\\ &= \text{fibs}(2) + \text{fibs}(1) + \text{fibs}(1) + \text{fibs}(0) + \text{fibs}(1) + \text{fibs}(0) + 1\\ &= \text{fibs}(1) + \text{fibs}(0) + 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 + 1\\ &= 1 + 0 + 1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 0 + 1 \\ &= 5 \end{align}\]

Look at how many calls we are making to the function! Even for such a low index, we call the function a dozen times.

It is clear that we are not making an efficient use of this sequence’s properties. There are multiple instances of the same value being recalculated in a single

call of the function. None of the function calls actually evaluate to an integer except fibs(0)

and fibs(1), and even these are called redundantly. More than that, this process starts all over when we need to calculate fibs(6).

The Fibonacci sequence using Memoization

What we need is a clean way to implement a dictionary that records all intermediate calls of the function so that each index of the sequence is calculated exactly once, and any future calls use this dictionary.

Here is where we can implement memoization. Surprisingly, we are going to be able to use the same function but will be altering it into a class that has access to a dictionary of previously calculated values. We start by defining the following class:

class Memoize:

def __init__(self, fn):

self.fn = fn

self.memo = {}

def __call__(self, *args):

if args not in self.memo:

self.memo[args] = self.fn(*args)

return self.memo[args]

Let’s break down what’s happening. The method __init__ initializes the class by

- storing the passed function as

self.fn - creating the dictionary

self.memo

The method __call__ is executed when the instance is called and checks if self.memo contains the function arguments then:

- if it does, we can simply return the value from the dictionary

- if not, the function is evaluated and added to the dictionary for future use

To initialize this class with the function fib we do the following:

@Memoize

def fib(n):

if n == 0:

return 0

elif n == 1:

return 1

else:

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

Here @Memoize is a decorator. This is simply a shorter way of writing fib = Memoize(fib)

to replace our original function with the new class. Now how will fibs(5) perform as compared to above? If fibs(4) and fibs(3) are in

self.memo it would be a single line!

For instance, after evaluating fibs(4) we can see that self.memo contains:

{(1,): 1, (0,): 0, (2,): 1, (3,): 2, (4,): 3}

so that if fibs(5) is called, the function will lookup fibs(4) and fibs(3) in

self.memo instead of the longer calculation shown earlier.

The performance benefit is astounding. Using timeit to measure our new function, we can produce the first 100,000 Fibonacci numbers with average time:

%%timeit

@Memoize

def fib(n):

if n == 0:

return 0

elif n == 1:

return 1

else:

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

times = []

for n in range(100000):

start = time()

fib(n)

stop = time()

duration = stop-start

times.append((n, duration))

Output:

291 ms ±7.94 ms per loop (mean std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)

(Please note that I am using Jupyter, the %% is a built-in magic command)

We can make this faster, but I’ll save that discussion for a future post as it is more related to mathematical rather than memory manipulation.

One last note that these numbers are huge, with the last number \(F_{99,999} \approx 1.60528 \times 10^{20898}\) being over 20,000 digits long! I tried to compute up to the one-millionth Fibonacci but my computer became unresponsive.

Lengths of Collatz Sequences

Now that we have a bit of a feel for things, let’s look at a slightly more complex sequence. Consider the following function:

\[ f(n) = \begin{cases} \frac{n}{2} &\text{if } n \equiv 0 \pmod{2}\\[4px] 3n+1 & \text{if } n\equiv 1 \pmod{2} .\end{cases} \]

We use this function to create a sequence by continually applying \(f\) until we reach a value of 1 (which causes a loop back to 1). For instance, we have:

\[ 13 \rightarrow 40 \rightarrow 20 \rightarrow 10 \rightarrow 5 \rightarrow 16 \rightarrow 8 \rightarrow 4 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 1 \]

The Collatz Conjecture is the statement that any initial starting value creates a sequence that will end at 1. Despite the apparent simplicity of its statement, this problem is considered one of the great open problems in mathematics, with even the great mathematician Erdős being quoted as saying: “Mathematics is not yet ripe enough for such questions.”

Nevertheless, it is easy to define the sequence in Python. Following Project Euler’s problem 14, consider the following question: Which starting number, under one million, produces the longest sequence?

I can define the following two functions:

def collatz(n):

if n == 1:

return 1

elif n % 2 == 0:

return n//2

else:

return 3*n + 1

def collatz_sequence(n):

sequence = [n]

while 1 not in sequence:

n = collatz(n)

sequence.append(n)

return len(sequence)

and brute force the solution:

lengths = [collatz_sequence(n) for n in range(1, 1000000)]

solution = lengths.index(max(lengths))

This takes approximately a minute and a half on my desktop, returning that the longest chain for initial values under one million begins at 837799 and produces a sequence of 525 numbers. This isn’t bad, but we can do better (even without thinking about the math more) by using memoization.

Lengths of Collatz Sequences Using Memoization

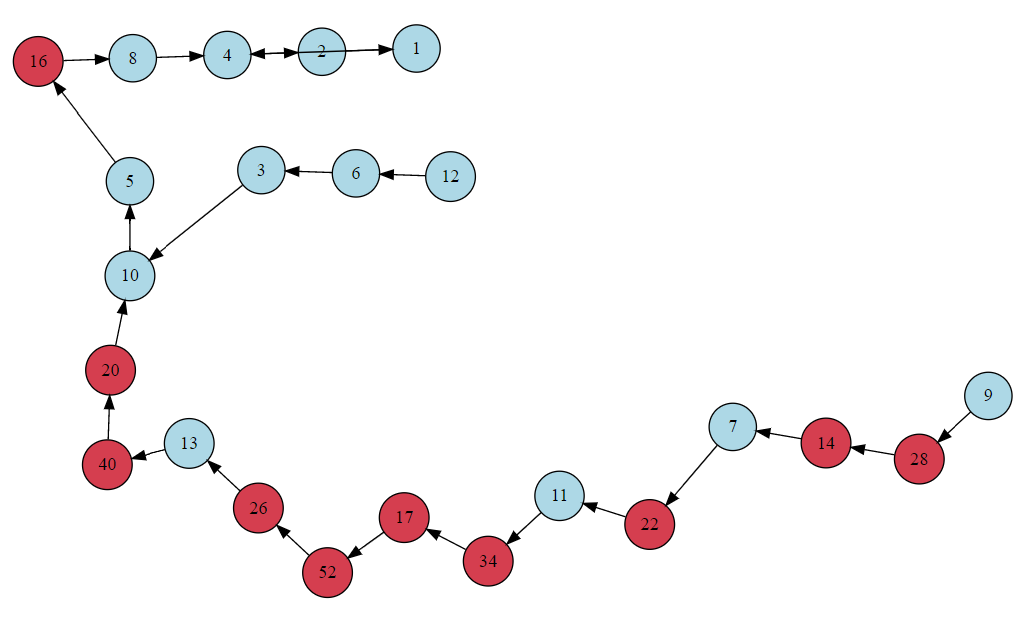

This is a little harder to mentally visualize, so let’s take a look at a diagram, which shows all sequences with length less than 20:

One thing we can notice is that there is a lot of repetition in our sequences, as they form large “branches” that split off at various points. For instance, every sequence in the diagram includes the subsequence

\[ 16 \rightarrow 8 \rightarrow 4 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 1 \]

So imagine for a moment that I have already evaluated collatz_sequence(16) and seen that it has length 5. Then if I were evaluating collatz_sequence(32)

or collatz_sequence(5), the starting points that have 16 as their next step, I know that the length will evaluate to \(1+5=6\), saving me several addition and subtraction operations. This is a perfect oppurtunity for memoization.

I can leave the collatz function as it is, but will need to slightly alter the memoization class and the function that computes the sequence length.

I actually can simplify the memoization class to:

class Memoize:

def __init__(self, fn):

self.fn = fn

self.memo = {}

def __call__(self, *args):

self.fn(*args, self.memo)

Notice that instead of the __call__ method checking self.memo it just passes the dictionary as an arguement to our function. For this problem,

I just felt it was easier to rewrite the function with the memoization dictionary as an arguement.

So I will now make the sequence function:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | @Memoize def collatz_sequence(n, cache): if n == 1: cache[n] = 1 return 1 copy = n sequence = [n] while 1 not in sequence: n = collatz(n) if n in cache: cache[copy] = len(sequence) + cache[n] break else: sequence.append(n) |

Let’s break down what’s happening. First in lines 2 through 8:

- If the initial value is 1, we add the key-value pair 1:1 to

self.memo - We make a copy of the inital number for later use with

self.memo - Initialize the list that will hold our Collatz sequence

Then in the while loop:

- We continue so long as our sequence has not reached 1

- We calculate the next value of the Collatz sequence

- If the next value is in

self.memowe know that this is the remaining length - If the next value is not in

self.memowe continue by appending to the sequence

Note that this class is meant to be called in numerical order to take advantage of the memotization. As an example, if we compute the length of the first 13 sequences with:

for n in range(1, 14):

collatz_sequence(n)

then collatz_sequence.memo will contain:

{1: 1, 2: 2, 3: 8, 4: 3, 5: 6, 6: 9, 7: 17, 8: 4, 9: 20, 10: 7, 11: 15, 12: 10, 13: 10}

The performance greatly improves. Computing the lengths and sequences with an initial value less than one million and again measuring with timeit:

%%timeit

@Memoize

def collatz_sequence(n, cache):

if n == 1:

cache[n] = 1

return 1

copy = n

sequence = [n]

while 1 not in sequence:

n = collatz(n)

if n in cache:

cache[copy] = len(sequence) + cache[n]

break

else:

sequence.append(n)

return len(sequence)

for n in range(1, 1000000):

collatz_sequence(n)

Output:

2.53 s ±22.5 ms per loop (mean std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)

A Small Improvement

However, we can easily make a small change that will give just a bit more improvement. Look at the dictionary above. What is it missing? We calculated through the sequence starting with 13, but we didn’t add any of these intermediate values to our dictionary! We can add a loop to capture these as well:

@Memoize

def collatz_sequence(n, cache):

if n == 1:

cache[n] = 1

return 1

copy = n

sequence = [n]

while 1 not in sequence:

n = collatz(n)

if n in cache:

cache[copy] = len(sequence) + cache[n]

break

else:

sequence.append(n)

for index, value in enumerate(sequence[::-1]):

cache[value] = cache[n] + index + 1

Now if we run the first 13 sequences again, self.memo will contain:

{1: 1, 2: 2, 3: 8, 4: 3, 8: 4, 16: 5, 5: 6, 10: 7, 6: 9, 7: 17, 20: 8, 40: 9, 13: 10, 26: 11, 52: 12, 17: 13, 34: 14, 11: 15, 22: 16, 9: 20, 14: 18, 28: 19, 12: 10}

We can visualize the change that we have made to the function by looking at the below graph, which is just a piece of the larger graph above. I have included all sequences that are generated from initial values 1 through 13. I have colored the initial values in blue and all other included numbers in red. Our first version failed to account for these additional numbers that appear in the sequence but are outside our range of initial values. We can see that in this particular case that we can store nearly twice as many values for future use.

Finally, we can run this new version for initial values of less than one million and use timeit again:

%%timeit

@Memoize

def collatz_sequence(n, cache):

if n == 1:

cache[n] = 1

return 1

copy = n

sequence = [n]

while 1 not in sequence:

n = collatz(n)

if n in cache:

cache[copy] = len(sequence) + cache[n]

break

else:

sequence.append(n)

for index, value in enumerate(sequence[::-1]):

cache[value] = cache[n] + index + 1

for n in range(1, 1000000):

collatz_sequence(n)

Output:

1.99 s ±43 ms per loop (mean std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)

Conclusion

As we have seen, the use of memoization can have a drastic effect on the performance of a program. At its heart, all of these optimizations revolve around understanding and exploiting the structure of a particular problem with the use of an appropriate data structure that reduces repeating calculations when at all possible.

As we will see in a later post, this same idea of exploiting structure has vast generalizations that allow us the work with general mathematical frameworks and translate these into data structures that take advantage of the common structure between seemingly disparate problems.

Code used in this article can be found here.